Science and faith are a harmonious pair that operate in unison on a shared path to truth, enriching and supporting each other, according to Catholic teaching expressed by Pope Francis and in the Catechism of the Catholic Church.

Professor George Mendz and Dr Rachel Bradley, two Australian Catholics with scientific expertise, recently shared their insights into the communal journey of science and faith, refuting modern culture’s assertion that science and faith are incompatible.

Debunking the myth

A lecturer and researcher in the School of Medicine at the University of Notre Dame Australia, Professor Mendz has always had a thirst for knowledge – something which he says science only provides a portion of.

“Science, with its limitations, provides some knowledge, but not ultimate knowledge,” he says. “Philosophy also allows you to get to knowledge from a different direction.”

Professor Mendz says ultimate knowledge, or truth, can only be derived from its source, which is God. And so, if God is the source of truth and science seeks to reveal the truth about material things, the two act in perfect harmony.

Professor Mendz says ultimate knowledge, or truth, can only be derived from its source, which is God. And so, if God is the source of truth and science seeks to reveal the truth about material things, the two act in perfect harmony.

“Always, when a scientific theory has backed a philosophy incompatible with Christianity, that theory has been proven to be wrong in time,” he explains.[1]

“Christianity is not proven by science, but good science will always align with Christianity. And Christianity, in the philosophical and the theological aspects, doesn’t need science to be proven.”

Professor Mendz’s words echo those of the Catechism, which affirms that “there can never be any real discrepancy between faith and reason”. It continues: “Since the same God who reveals mysteries and infuses faith has bestowed the light of reason on the human mind, God cannot deny himself, nor can truth ever contradict truth,” (n.159).

But how has modern culture managed to convince so many that science and faith are at odds?

Dr Bradley, a Tasmanian GP, says the view that science is the only legitimate way to find truth has been perpetuated for so long that it is now accepted by many without question.

“It's one of those urban myths that people just take on without really thinking about it,” she says.

“If you repeat the same truth over and over again, people just believe it, and that’s been the case I think for lots of things with science and faith.

“Many people put anything to do with faith into a very primitive worldview that excludes scientific inquiry.”

Further evidence for the harmony of science and faith can be found in the history of the discipline and its key proponents.

Further evidence for the harmony of science and faith can be found in the history of the discipline and its key proponents.

“Modern science really came to birth from a Christian society,” Dr Bradley says. “Many great scientists, up to quite recently, were Christian.”

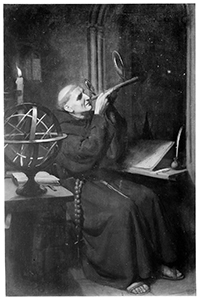

These include the 13th-century Franciscan Fr Roger Bacon, a major pioneer of the scientific method; Fr Gregor Mendel, an Augustinian friar known as the father of modern genetics; the astrophysicist Fr Angelo Secchi SJ; inventor and mathematician Blaise Pascal; the Catholic astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus; and Fr Georges Lemâitre, the formulator of the “Big Bang” theory.

In more recent times, notable Catholic scientists include American physicist Stephen Barr, 2012 Nobel Prize recipient Brian Kobilka, Polish mathematical physicist Fr Michal Heller and clinical psychologist Robert Wicks.

Science as a tool for evangelisation

As a committed Catholic who is immersed in evidence-based practice in her work, Dr Bradley says science has enhanced and strengthened her faith.

“I’ve never personally seen any contradiction between a scientific outlook and my faith,” she says. “The more you learn about the intricacy and the beauty of creation, the more it can actually validate your faith.”

Dr Bradley says science can be “incredibly useful” in the task of evangelisation.

“Especially with the physical sciences, the more we find out… the more I think faith is bolstered,” she says.

“For example, the unusual structure of water molecules. Water doesn’t respond like most liquids, and the way that it responds just so happens to mean that life can exist on earth.

“Real scientific inquiry just brings you into contact with the beauty of the universe, which can be something that draws the heart and mind to God.”

For Professor Mendz, science can be a way to open up conversations and prompt reflection upon deeper questions of meaning and ethics with his university students and colleagues.

“My approach to this is very simple,” he says. “First of all, let’s go to the principles – where you start, where I start.

“The conversation might start with ‘My grandfather was very ill and wanted to die’. Then we might talk about the ethics of prolonging life by medical means as opposed to choosing to end one’s life, and the scientific arguments for both positions.

“Eventually we get to the question of ‘What do you think is a human being?’ Sometimes the principles are correct, but the logic is faulty.”

Science and faith support each other

“Science can purify religion from error and superstition; religion can purify science from idolatry and false absolutes.”

These words from Pope St John Paul II, in a letter to the director of the Vatican Observatory in 1988, demonstrate the Church’s view that science and faith can support each other.

Indeed, in the realm of ethics and morals, the Church often uses science to inform its teachings. For example, the methods of natural family planning endorsed by the Church are based on scientific research about fertility.

Professor Mendz, who has published research papers in bioethics and has a particular interest in end-of-life issues, says discussions around topics like euthanasia cannot begin from a moral or ethical perspective.

“Usually emotive arguments are raised against euthanasia,” he says. “But in my research papers, we always start with what the science says, and particularly what the science doesn’t say, and then we go onto the ethics.”

Professor Mendz has also published research in the ethics of embryology. While he is morally, philosophically and ethically opposed to embryo research, he says convincing the scientific community requires a scientific argument, rather than a moral one.

Professor Mendz has also published research in the ethics of embryology. While he is morally, philosophically and ethically opposed to embryo research, he says convincing the scientific community requires a scientific argument, rather than a moral one.

“Most legislation around the world forbids embryo experimentation beyond 14 days,” he says. “The rationale – which is biologically, scientifically, logically, and philosophically wrong – is that one cannot say the embryo is an individual for sure until after 14 days.

“But this has the wrong biology. It’s based on a model put forward in the 1950s, with all the embryology they knew then, which is much, much less than we know now, and also it was a purely hypothetical model.”

In this way, scientific information can be used to support a faith-based, moral position. But Professor Mendz says too often society tries to use science to make a moral or ethical argument.

“Science is reduced to material objects, but as soon as you want to explain something that may not be a material object, then you are going to fall short all the time, because you are trying to explain things without the right instruments,” he says.

For all its advances in recent times, there’s no doubt science still has its limitations. But no matter the field of science, when it operates harmoniously with faith, the pair can lead humanity to truth.

Images: Unsplash; Roger Bacon in his observatory at Merton College, Oxford. Oil painting by Ernest Board. Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark. Source: Wellcome Collection. https://wellcomecollection.org/works/ej92m7hc

Words: Matthew Biddle

[1] Professor Mendz says an example, from the 17th century to the first half of the 20th century, is scientific racism or biological racism, stating that the human species can be divided into different taxa. Not that there are different races with various physical characteristics, which is a fact, but that there are races superior to others. It was rejected by Catholic theologians and others because, among other things, this theory jeopardised the universal value and application of Redemption. Needless to say, scientific racism has been found false, albeit amply espoused by European and North American elites for quite some time.